Infectious Agents: Clostridium difficile

Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) is a Gram-positive, spore-forming, obligate anaerobic bacterium. It is primarily found in the gut microbiota of humans and animals but can act as an opportunistic pathogen in immunocompromised or hospitalized patients (Rupnik et al., 2009). Its ability to produce spores makes it highly resistant to environmental stress, enabling long-term survival in healthcare settings.

The biological adaptations of C. difficile, such as spore formation and environmental resilience, make it highly effective in maintaining long-term survival and facilitating transmission. However, this effectiveness is contingent on specific conditions, such as antibiotic use or immune suppression, which limits its infective potential in healthy populations.

Clostridium difficile spores are highly resistant to many standard disinfection procedures, such as alcohol-based sanitizers and bleach solutions, allowing them to persist on surfaces for extended periods. Under optimal conditions, C. difficile spores can survive on environmental surfaces for up to 5 months (Lessa et al., 2015). They are particularly resilient to desiccation and can endure harsh conditions, including exposure to heat and disinfectants that do not target spores effectively, increasing the likelihood of patient-to-patient transmission in healthcare settings (Evans et al., 2012).

The bacterium’s reliance on external triggers, such as bile acids for spore germination, introduces variability in its infectivity. This dependency suggests that while C. difficile is a robust pathogen, its pathogenicity is not universal and may be influenced by host-specific factors, limiting its reliability as a consistent infectious agent.

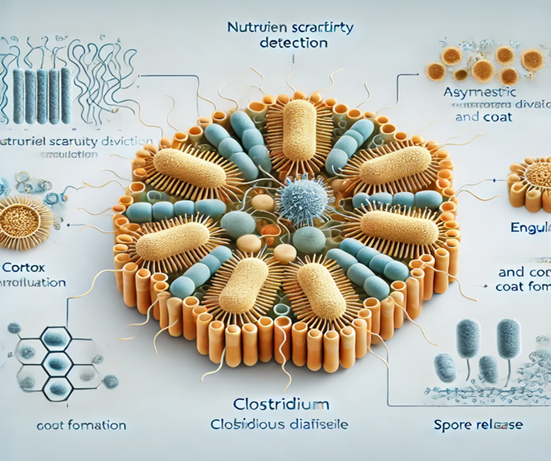

This figure illustrates the five stages of spore formation in Clostridium difficile: nutrient scarcity detection, asymmetric division, engulfment, cortex and coat formation, and spore release. Each structural component, including the spore coat, cortex, core, and exosporium, is labeled to emphasize their roles in survival and transmission.

What Are Spores?

Spores are metabolically dormant structures formed by bacteria such as C. difficile in response to nutrient depletion or other environmental stresses. These structures consist of:

• Spore Coat: Provides resistance against chemical and enzymatic degradation.

-

Cortex: Protects the spore from osmotic pressure changes.

-

Core: Contains dehydrated cytoplasm, ensuring the preservation of genetic material and enzymatic activity.

-

Exosporium: Aids in adhesion to surfaces and interaction with host environments (Barbut & Petit, 2001).

This structural complexity is not merely a passive adaptation but an active strategy that allows C. difficile to withstand unfavorable conditions and re-establish infections when conditions improve. The evolutionary refinement of sporulation underscores its role as a defining feature of C. difficile’s success as an infectious agent.

Formation of Spores

Sporulation is a multi-step process that allows C. difficile to enter a dormant state when environmental conditions become unfavorable. Key steps include:

1. Detection of Nutrient Scarcity: Activation of sporulation genes.

2. Asymmetric Division: Segregation into a mother cell and a forespore.

3. Engulfment: The forespore is enveloped by the mother cell.

4. Cortex and Coat Formation: Layers are deposited to fortify the spore.

5. Maturation and Release: The mature spore is released, enabling survival in adverse conditions (Paredes- Sabja et al., 2014).

References

Hota, S. S. (2007). Contamination, disinfection, and cross-colonization: Are hospital surfaces reservoirs for nosocomial infection? Clinical Infectious Diseases, 39(8), 1182-1189.

Kelly, C. P., & LaMont, J. T. (2008). Clostridium difficile—more difficult than ever. New England Journal of Medicine, 359(18), 1932-1940.

Leffler, D. A., & Lamont, J. T. (2015). Clostridium difficile infection. New England Journal of Medicine, 372(16), 1539-1548.

Create Your Own Website With Webador